Interest in traditional Czech beer culture has been growing outside of its homeland. This is in part due to a general renewed interest in varying lager styles of beer. It has been bolstered by Instagramable pictures of varying pours from Lukr side-pull faucets.

Here in the US, the breweries and bars with attention to detail serve Czech-style beer in a glass style generally found in the Czech Republic. Typically, that means a Tübinger. Yet this certainly isn’t the only glass used, and as their beer culture is evolving, it’s interesting to see glassware choices offered by establishments old and new. Before we get to that, let’s start with a quick recap of the Tübinger.

The Tübinger is a specific handled beer glass with dimples. Its origins go back to the late 1800s in Germany, but it’s a rarity there and it is much more common in the Czech Republic these days. Its design lends itself particularly well to the traditional hladinka pour, which you can see in the beers below. A proper pour will result in the foam ending right around where the dimple portion of the mug begins.

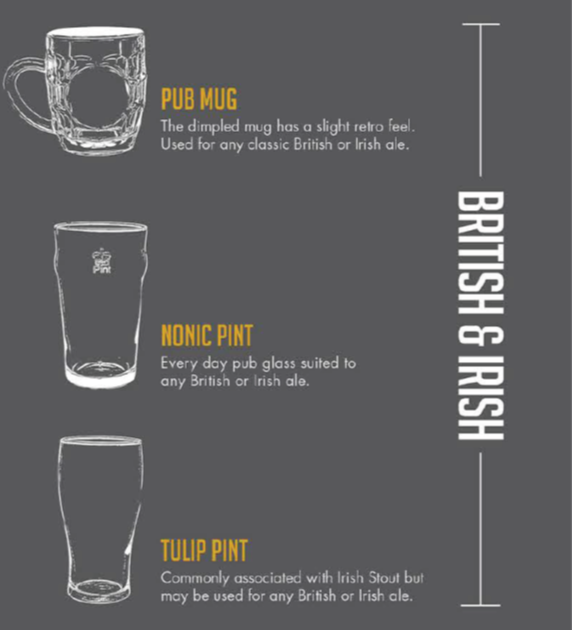

You can read more about the Tübinger here. It’s important to note that this mug is not the same as the British dimple mug and its modern replicas. There’s no need to be snobby about it. It’s just worth knowing that they’re different mugs from different cultures.

Branded Tübinger mugs by the Czech breweries Budějovický Budvar, Únětický pivovar and Vinohradský pivovar. Source: https://www.instagram.com/

In the Czech Republic, breweries like Budějovický Budvar (aka Czechvar in the United States), Únětický pivovar and Vinohradský pivovar have branded Tübingers. Even Pilsner Urquell has one. But Urquell and Budvar also have the luxury of creating proprietary mugs. For younger breweries with fewer resources that feel the impacts more from glass shortages and long production times, alternative styles can be appealing. Especially if they’re breaking from old traditions. More on that later.

Given Urquell’s size and popularity, their mug is one of the most iconic Czech beer glasses (to be clear, Urquell sells a variety of glasses, but the mug pictured below is the most well-known and ubiquitous). While the design is distinctive, it incorporates the elements commonly shared by most Czech beer glasses.

Typical Czech beer glasses are found in 0.3 (třetinka) to 0.5 (půllitr) liter sizes. They are handled mugs with thick glass, which some note is important to maintaining temperature (others disagree with this sentiment).

The mugs are generally referred to as a "krýgl", though they are sometimes called “sklenice s uchem”, which means “glass with an ear”. Kozel is known for its horned (rohatá) mug. Overall, these glasses work well with the increasingly popular Lukr faucet as noted by Mirek Nekolný, a Pilsner Urquell Master Bartender.

While mugs and side-pull faucets have been around in the Czech Republic for a while, Lukr has only been around since the 1990s. Its unique design, with a ball valve, flow control regulator (compensator), and tap screen, create decadent foam.

According to Nekolný, tumblers (štucs) became popular in the Czech Republic in the 90s. Perhaps the shift back to mugs is due to the rise in popularity of the Lukr faucets and their inherent compatibility with stout-shaped glassware. The reason for this is the shape and length of the faucet, which is inserted into a glass when pouring beer. This is a practice discouraged in other drinking cultures.

Like Urquell, Budvar sells a variety of drinkware. However, the brewery released a new mug in 2020 (shown above) and has made it a point to highlight it ever since. It’s clearly something that’s important to the company.

Gabriela Kudrnacova, Budvar’s brand manager, says “the glass is one of the most impactful items we possess as it is in direct and natural contact with the customer.”

The new mug is manufactured by Sahm. In addition to the custom drinkware they produce, Sahm also makes several other commonly used glasses embraced by the Czech beer community. Some of these are depicted below.

Czech beer culture continues to evolve though, and some are looking outside of their culture for inspiration. Pivovar Matuška is an excellent example. The brewery began in 2009 and makes a variety of beer styles. They do make traditional Czech lager, but they also brew IPA, Stout, Wheat beers, ESB et. al. To accommodate these varying styles, the brewery offers several types of glasses.

An array Pivovar Matuška glassware reflecting its multicultural portfolio. Source: Pivovar Matuška.

The range of glasses serves their portfolio well, but the brewery isn’t militant about which should be used for a particular beer. Matuška Managing Director Matěj Šůcha notes “our customers can choose what type of glass they prefer. We are not pedantic in a way that if someone orders a keg of lager and a case of Nonic glasses, we don't tell them they can't do that, but we do offer some info about the glasses so they know what it should be used for.”

Matuška Co-owner and Head Brewer Adam Matuška is also a founder of the brewery Dva Kohouti. This newer venture is in partnership with the Ambiente restaurant group, which is also behind the Lokal tank pub chain and Pult, a craft beer bar.

Dva Kohouti is similar to Matuška in the range of beer styles they make. However, their glassware program differs. Dva Kohouti solely uses the dimple mug that is closer in design to the traditional British dimple mug. In a 2018 Instagram post, the brewery recognizes the mug is in the English style, but notes they find it ideal to serve their variety of beer styles.

Dva Kohouti uses a British-style dimple mug for its Czech and non-Czech style beer. Source: Dva Kohouti.

Opened in 2013, Vinohradský pivovar also follows these beer production trends. When it comes to glassware though, they use the Tübinger for their Czech lager. A shaker pint (aka straight glass) and a Teku glass meets the needs for their other brews.

In addition to their Tübinger shown earlier, Vinohradský pivovar also makes use of the shaker pint (aka the straight glass) and the Teku to serve their range of beers. Source: Vinohradský pivovar.

The recently opened Pult typically offers six lagers on tap and packaged offerings of varying styles from around the world. The bulk of their beer is served in a simple, unbranded panel mug. A stemmed glass is used for their other beer offerings.

This is reflective of one way to deal with the changing nature of Czech beer culture. Though not a tied house and free to serve an array of styles (they notably have both Pilsner Urquell and Budvar on tap, which is uncommon), Pult continues to keep its glassware program streamlined. This is traditional in a sense and has certain efficiencies. It’s in contrast to what you find at a beer bar in Belgium or even the United States.

Amid the thriving Czech beer scene, the Tübinger is still common, and likely will be for some time. Again, many breweries offer this mug with their branding. They’re common in pubs and restaurants, and offer an accepted and reliable alternative for tied pubs that, for example, may be connected to Pilsner Urquell and use their proprietary mug, but offer one or two other beers. Jan Fišera of Únětický pivovar puts it in simple terms, “this type of glass has been tried and tested for us for a long time and we are satisfied with it.”

One last item of note that came up repeatedly in the responses received for this post is glass/serving size. In the past, 0.3 and 0.5L have been common serving sizes. However, 0.4L is rising in popularity as the only serving size for some. Kudrnacova at Budvar notes this is “quite a thing in modern places” and Šůcha at Matuška says “people have gotten accustomed to it quite easily.”

For Dva Kohouti, their British-style dimple mug is a pint, which means when served with a proper amount of foam, consumers receive a 0.4L beer.

This is also the serving size at the famed brewery/restaurant U Fleků. While you can buy a variety of drinkware in differing sizes in their gift shop, they only serve their beer in an unmarked 0.4L Salzburg mug by Sahm.

Support for the 0.4L serving size is not universally accepted though. Fišera notes that many find it one sip too much, or one sip not enough. I see merit to all though and find it best for each establishment to pick whatever meets their needs.