Mexican Lager: History and Appropriation

Mexican Lagers are fairly common offerings at breweries across America now. This is particularly true around Cinco de Mayo. Unfortunately, these releases often come with artwork that appropriates Mexican culture. To make matters worse, they frequently spread stories about what Mexican Lager is, including its history, that is often wrong or misleading.

Culturally appropriative imagery. If you see a beer with this kind of stuff on the label, beware. Source: the internet.

(Two notes upfront. First, for my vegan and vegetarian friends, this post contains pictures of Mexican food that includes meat. Second, I’ve flirted with this subject before in an earlier post on Vienna Lager, which can be viewed here.)

So, what is Mexican Lager? It’s often said that it’s a pale lager (but sometimes amber, sometimes darker), made with adjuncts. These days, that primarily means a corn-based product. This definition is true, but also broad and doesn’t distinguish Mexico from a number of other lager producing countries. This includes the United States, which began making adjunct lager shortly before Mexico did. Accordingly, organizations like the Beer Judge Certification Program explicitly place Mexican Lagers under the International Pale and International Amber Lager categories instead of creating a distinct classification. Darker Mexican lagers fall under the International Dark Lager category.

American lager brewers began using adjuncts because the six-row type of barleys domestically available had challenges comparatively to the two-row barleys beer-drinking cultures in Europe were accustomed to. Six-row barleys were high in proteins and tannins and contributed a haziness and astringency to beer.

Adjuncts like corn and rice helped make a smoother, clearer beer, while still contributing fermentable sugars. Despite the idea that they were a way to cut corners, corn and rice were at times more expensive than barley, but worth it as it resulted in a better product than beer made with all six-row malt.

The type of adjuncts used in typical lager brewing don’t often contribute a significant impression in terms of flavor themselves (though they will help dry out malty sweetness). However, they replace fermentables that do. This can result in a less flavorful beer than one made solely with barley. Sometimes less is more though.

Brewers that either worked or trained in the United States brought this type of brewing with them to Mexico in the late 1800s to early 1900s.

Corona, the classic Mexican Lager that includes corn in the grain mix. Sure, it’s great for the beach or Cinco de Mayo, but it’s also enjoyable year-round. Hold the lime and the sombrero.

Before diving in further, it’s important to note that most of the documentation I have reviewed was written in English and from sources that are overwhelmingly not from Mexico. A few of these references did rely on research that included Mexican sources. I bring this up as it’s important to exercise a bit of caution due to whitewashing, especially with older literature influenced by ideology we know today to be faulty. I have tried my best to see through biased and bigoted sentiments.

An example is how some described the native drink pulque in comparison to beer. Pulque is a fermented beverage made with sap from the agave plant. It has a similar ABV to typical beer. Historically, pulque was widely consumed in Mexico. Reminiscences of Mexico (in Frank Leslie’s New Family Magazine, October 1858) notes, “the inhabitants of the Mexican capital can no more exist without pulque than New York Germans without lager bier.”

With no legitimate basis, the 1903 edition of One Hundred Years of Brewing describes pulque as "unwholesome". “Pulque” it says, “is consumed by the proletariat, who drink it out of large rubel, or tin cups, until they are besotted.” Referring to the growth of the Mexican brewing industry, the 1901 edition of the book states “the end of the nineteenth century already witnesses the erection of several new breweries. Let us hope, then, that our precious barley-juice may soon be established as the favorite drink of the Mexican, and that the death sentence be pronounced on pulque.”

Lager beer in its early days in Mexico was much more expensive than pulque and unaffordale to most Mexicans. Yet it seemed to the authors of One Hundred Years of Brewing and others that Mexicans should be thankful to them for bringing a more wholesome beverage to their country. Just one more way to conquest a culture.

Mexican Lager History

Returning to the question of what Mexican Lager is, it’s important to understand the industry’s history. I’m including a particular focus on two breweries, Cervecera de Toluca y México and Cervecería Cuauhtémoc, as they were pivotal in the industry’s growth.

People of Mexico have long enjoyed fermented beverages of varying kinds. Among others, these include tequila, mezcal, the previously mentioned pulque, and tesgüino (the first three are made from the agave plant. Tesgüino is a form of beer made with corn). It is often said that beer was first introduced to the area by the Spaniards in the 16th century. That may be true if you are discussing beer in the European tradition, but tesgüino was made well before the Spanish arrival. European-style beer did not become a notable part of Mexican culture until a few centuries later. This was due to lager.

The 1800s were a turbulent time in Mexico, beginning with the fight for independence from the Spanish in the earlier part of the century. In the decades following the Mexican War of Independence, the country became home to immigrants from what is now Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, among others. Some began brewing beer locally, while others imported it from their native lands. The beer these immigrants brewed was ale.

In 1864, the Second Mexican Empire was created by the French, who selected an Austrian, Maximilian I, to be emperor. It was short-lived, and Maximilian was executed in 1867. However, his very brief presence has generated stories that include him bringing his love of Vienna Lager to Mexico. To satiate his thirst, he brought brewers with him to make the beloved Austrian beer. However, there’s no evidence this actually happened. This is not surprising as the lack of refridgeration in Mexico at that time made lager production incredibly difficult since it requires cold temperatures for fermentation and aging.1

— —

The history of the lager brewing industry in Mexico begins with Santiago Graf at Cervecera de Toluca y México. Toluca, or what became Toluca, was founded in 1865 by Agustin Marendaz. Both Graf and Marendaz were of Swiss origin. Marendaz was making a type of ale called Cerveza Sencilla when Graf acquired the brewery in 1875 (some accounts say 1879), but it would be a few years before lager would be produced.2,3

Due to the construction of a rail line between Texas and Mexico shortly after Graf took over, he was able to import the first ice machine into Mexico to his brewery in the early 1880s. This allowed him to produce the first lager made in Mexico as far as I know. Dates in the records vary a little, but it’s possible the actual brewing of lager beer began in 1884 or 1885, and the release of the beer to the public was in 1885 or 1886.

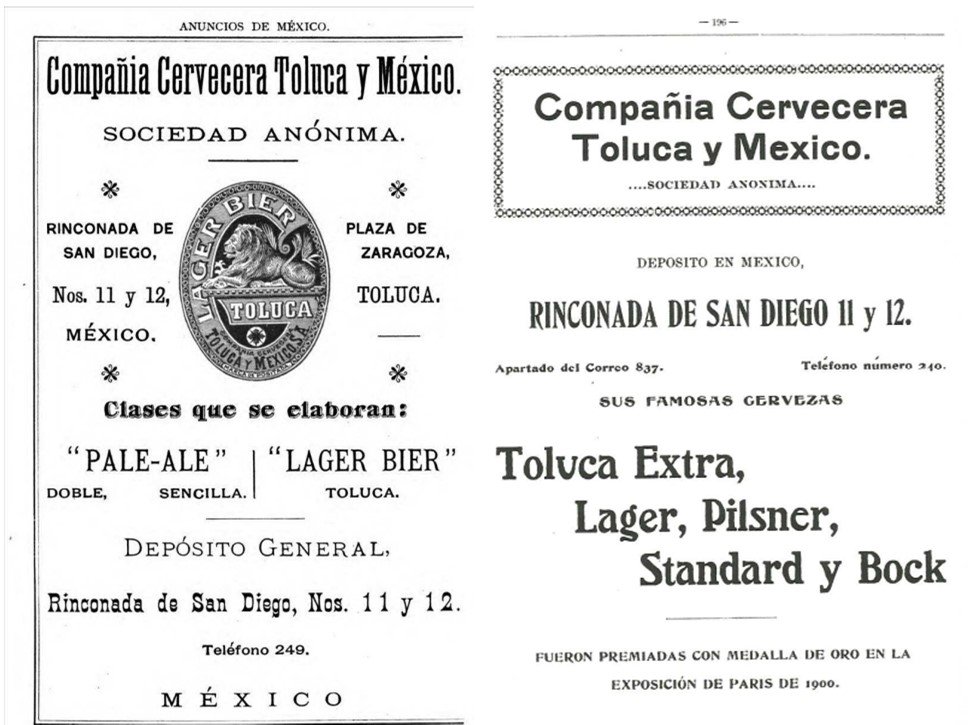

It’s unclear what type of beer this first release was, but within a few years, Toluca was making a variety of lager styles. One ad notes Toluca Extra, Lager, Pilsner, Standard and Bock (note the absence of Vienna). Ales were still part of the portfolio for a little while. An early advertisement with Toluca Lager refers to two types of Pale Ale, including Doble (double) and Sencilla.

Early ads for Cervecera de Toluca y México. Source: Wiecherspedia

It also made “steem beer”, according to One Hundred Years of Brewing (1901). This account may very well be referring to Dampfbier (which translates to steam beer). There are a variety of stories about what Dampfbier is, or was. The term in this case may just refer to a beer brewed with steam as a heat source.

Toluca’s success led to additional investment in 1890, which resulted in tremendous growth. For a couple of decades, it was one of the leading breweries in the country, making around 100,000 barrels of beer per year. For reference, this is exponentially more than most independent breweries make today. Their success led to American breweries such as Anheuser-Busch being “crowded out” of the market in Mexico City, according to One Hundred Years of Brewing (1901).

Toluca began producing the amber lager Victoria in 1906. This beer is still in production, and it’s one of my favorite Mexican beers. Some erroneously refer to Victoria first being brewed in 1865 when the brewery opened. The Victoria website itself, along with other marketing, is misleading as it insinuates this. Oddly enough, the website also notes the introduction in 1906.

Two early ads for Victoria. Of note is how one explicitly states the beer is for the aristocracy. The other states the hops and malt are from Munich. Source: Wiecherspedia

A fitting pairing. Victoria, with its origings connected to two Swiss immigrants, and enchiladas suizas, or Swiss-style enchiladas.

Cervecería Cuauhtémoc was founded in the early 1890s and production began in 1891. The name Cuauhtémoc comes from the Aztec ruler who bravely defended indigenous people from the Spanish in the 1500s.

It appears their first beer was released to the market in 1892. The brewery was started by Francisco Sada, Isaac Garza, and José A. Muguerza of Mexico, along with Joseph M. Schnaider of St. Louis. Schnaider came from a successful brewing family and had solid experience in the business. Ignoring the three Mexican owners, the 1901 edition of One Hundred Years of Brewing notes him being referred to as the “beer king of Mexico”.

Within a few years, the brewery was winning awards all around the world with its Carta Blanca brand, including at the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893 (the World’s Fair), which took place in Chicago. Cuauhtémoc was the brewery that propelled Mexico into the international realm of brewing, and it was with this pale lager that to this day proudly notes on the label “Gran Premio de Chicago 1893”.

By the turn of the century, they were already making around 100,000 barrels per year, according to both the 1901 and 1903 editions of One Hundred Years of Brewing, and were in the process of expansion. By 1910, they were up to 300,000 barrels.

The 1903 edition indicates the brewery was making light and dark “American” beers. It’s unclear what is meant by American beers, but it may very well mean adjunct lager. Cuauhtémoc was using rice, but they were definitely influenced by European brewing traditions. The brewery had a Munich-inspired brand called Salvator, and, later, Bohemia (1905).

A 1901 article by WM. J. Bischoff in Letters on Brewing Vol.1 describes the brewery employing 800 men. According to the article, the brewery’s success enabled the company to pay the staff well, such that they were able to purchase Cuauhtémoc instead of “poison” like pulque.

The brewery’s growth was incredible, and they established brands early on that are still in existence today. They are Mexico’s oldest beer brands.

Historic Carta Blanca advertisements. The first being a bit bizarre. Source: Pinterest. The second from http://fermintellez.blogspot.com/ “Carta Blanca, it’s a pleasure”.

A Cervecería Cuauhtémoc booth at a 1907 fair in Madrid. The booth indicates the brewery had previously won awards in places like Chicago, Paris, St. Louis, Milan among others. From the book Don Isaac Garza by Edgardo Reyes Salcido.

The rise of the lager beer industry flourished during the prosperity of the Porfiriato, the era of the dictator Porfirio Diaz (1876-1910). But prosperity was not evenly distributed, and those not on board with Diaz did not fare well. Publications in the US did not see this as an issue and welcomed the change brought by Diaz. Indeed, there were a number of people in the US who financially benefited from the Diaz regime.

Ever since the very beginning of lager brewing in the country, the industry has been big business. Small operations simply couldn’t get far given the high costs associated with starting a lager brewery, particularly without support from the goverment.

The prosperity was put on pause with the overthrow of the Diaz regime, which was followed by a decade of revolution. The brewing industry suffered during this period, including hard times for Toluca which withered until it was acquired by Grupo Modelo in 1935 (Modelo was founded in 1922).

Once peace was established in the 1920s, the landscape had changed with a handful of brands rising in prominence (i.e. Cuauhtémoc, Moctezuma and Modelo) and others left behind. The timing was great for those that survived and for new ones, such as Modelo. At this time, Prohibition was in effect in the United States, which created demand for smuggled Mexican beer. It also encouraged Americans to visit Mexico to freely enjoy beer, and it eliminated competition from US imports. Also, Mexican brewers were able to purchase brewing equipment from closed US breweries at a discount price.

It’s around this same time that scholars Susan Gauss and Edward Beatty in “The World’s Beer: The Historical Geography of Brewing in Mexico” (The Geography of Beer: Regions, Environments, and Societies) note breweries “’Mexicanized’ production by developing internal technical expertise and by diversifying and integrating their investments into ancillary processes. The well-known Garza Sada group in Monterrey, owners of the Cervecería Cuauhtémoc, commonly sent their children and the firms technicians to study abroad.” Luis Sada, son of one Francisco Sada, was sent to the United States for training at the Wahl and Henius Brewing Academy in Chicago.

Wahl and Henius was connected to the growth of the Mexican lager industry. According to One Hundred Years of Brewing (1901), all the early lager breweries in Mexico had brewers that had trained at Wahl and Henius except Toluca. This may have been an exaggeration, which is reflected in the 1903 edition of the book that broadens this statement to say that aside from Toluca the brewers were all from America. Again, this may have been an exaggeration and/or misleading as well.

Isaac Garza’s son, Eugenio Garza Sada helped bring the training element home by establishing the Instituto Tecnologico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey in 1943. The institute enabled Mexicans to achieve the type of training to run a successful brewery, among other professions, without having to leave Mexico.

With all this change, Gauss and Beatty note, “between the 1930s and 1950s, Mexico became a nation of beer drinkers.” The campaign against pulque was successful and most pulque bars (pulquerias) closed by this time, though they didn’t completely disappear.

As noted above, Grupo Modelo was created in the 1920s, a few decades after the birth of the lager brewing industry in Mexico, and it came out swinging. The brewery brought in Adolf Schmedtje, a brewer from Anheuser-Busch, who created Corona and Modelo. (Schmedtje’s mother was Aldophus Busch’s niece). The brewery was created with the capability of producing 300,000 barrels per year.

Modelo went on to acquire Estrella and Pacífico in the 1950s and was ultimately acquired itself by AB-InBev in 2012. Similarly, Cuautémoc, which had merged with Moctezuma (maker of Dos Equis) in 1985, was acquired by Heineken in 2010.

A dish influenced by Middle Eastern immigrants, tacos árabes are traditionally made from spit-roasted pork (shawarma) and served on a pita. The Mexican restaurants in my area use flour toritallas. The dish has a little kick with a chipotle salsa, and is rinsed down nicely with a cold Pacífico.

Ingredients

It’s true that adjuncts are a notable part of Mexican Lager. In its earliest days, the use of adjuncts in Mexican Lager reflected the American beer industry. Most breweries imported grain from the US and Germany. They faced the same challenges with six-row barley noted above. Early on, some breweries like Toluca and La Perla were making their own malt, according to both editions of One Hundred Years of Brewing.

The 1901 edition of One Hundred Years of Brewing noted that Mexican lager was being brewed with a grain bill including fifteen to thirty percent rice. Some brewers may have used more or less than this. Several accounts describe domestic rice being high quality, and Toluca and Cuauhtémoc both used rice in these early days. The book also explicitly stated Toluca did not use corn. However, at some point, most if not all shifted to corn-based adjuncts.

Writing about Mexican Lager in 1901, Adolph Dietsch of Cervecería Cuauhtémoc stated in ‘Beer Breweries in the Republic of Mexico’ (Letters on Brewing Volumes 1-2) “in general, there are two kinds of native lager beers, the Münchener (decoction) and the Pilsner (infusion) beers.” For the former, he noted ingredients were “almost exclusively” from Germany and Austria. One oddity is that he mentioned the malt was made from Chevalier barley, a heritage barley from England.

For the Pilsner-style beers, he distinguished these from the Münchener style beers by noting the addition of “raw cereals” to the grain bill, specifically citing rice. This could support the suggestion that some beer styles did not use adjuncts. He also noted the use of Bohemian and Bavarian hops.

Cuauhtémoc’s Bohemia is a wonderful example of a pale Mexican Lager. It goes really well with a spicy Torta Ahogada, that blurry hot mess in the background. In this case, hot mess is a wonderful thing.

There’s not a whole lot in the records I’ve searched regarding yeast. However, in the book Taste, Politics, and Identities in Mexican Food, the chapter “Dos Equis and Five Rabbit: Beer and Taste in Greater Mexico” notes the following regarding yeast in the early days of Mexican lager brewing, “the preferred variety of brewer’s yeast in Mexico was Wahl and Henius’s pure lager culture, known as Chicago Number 1.” I’m curious if White Labs’ Mexican Lager Yeast (WLP 940) has any connection to this Wahl and Henius strain.

The Mexican government placed high tariffs on beer and beer-related imports during the early days of lager brewing (for some reason, an exception was made for hops). This cost the breweries large sums of money to obtain equipment and ingredients, but also forced them to begin producing some of their needs locally. However, it gave them a financial advantage over imported American beer.

Though this post primarily discusses the industry historically, I can’t help but mention water. Like yeast, it’s not really mentioned in the records I’ve reviewed. But in recent times, the country has been hard hit by droughts, raising serious health concerns. The breweries have largely been unfazed. This past summer, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador stepped in announcing that brewing operations would cease in the northern part of the country. He hasn’t actually enforced this, but feeling the pressure, breweries are looking for ways to use less water and ensure they are providing some for the community. Whether they’re doing enough is a subject for another forum.

Today

Water challenges aside, the big breweries in Mexico, albeit now owned by companies overseas, continue to do well and continue to be a part of the worldwide beer-drinking culture.

Small, independent brewers are slowly becoming a presence as well. One potential benefit of the now international ownership of the larger breweries is a somewhat less combative attitude toward independent brewers. Most of the small brewers are making ales and appear to have little interest in lager, let alone adjunct lager. It seems very reminiscent of the independent beer scene in the United States in its first few decades of revival.

One brewery of note that has taken an interest in lager is Cervecera Hércules, particularly at their Lagerbar location in Mexico City. Their portfolio is diverse, but at the Lagerbar, it’s strictly bottom-fermented beer on the menu. This includes a 100-percent Vienna malt Vienna Lager and a pale lager made with corn.

Cans of adjunct lager and Vienna Lager (made with Vienna Malt and no adjuncts) by Cervecera Hércules. Images: Cervecera Hércules

In addition to traditional and contemporary beer mentioned thus far, there’s another beer tradition that’s worthy of mention. Michelada. Maybe you’ve seen a can of it at your local convenience store. A Michelada is a beer cocktail that varies widely based on who is making it. They can be salty, spicy, sweet and sour. Typical ingredients beyond beer include lime juice, spices, hot sauce, and tomato juice, but again, they will vary as people like to add their own creative touch. They’re somewhat reminiscent of a Bloody Mary and often used as a hangover remedy. Most major breweries make a packaged version, but one of the greatest parts of a freshly made Michelada is the spectacle. They can be really ostentatious. They’re also much better tasting than the packaged versions.

Examples of the beer cocktail Michelada. Source: Mariah Tauger LA Times.

Some of Modelo’s canned Micheladas. Source Modelo

Finally, though it’s not beer, since I mentioned it earlier, it should be noted that there has been a resurgence of pulque. A new generation interested in native traditions has breathed life into the drink that saw a sharp decline as it was replaced by beer in the mid-twentieth century. Now, new pulquerias are popping up, and manufacturers have managed to create packaged versions of the drink with a notoriously short shelf life. They can even be found in certain places in the United States.

— —

The history of lager brewing in Mexico is nothing short of impressive, and Mexican Lager is something that should be celebrated. The country is now the largest exporter of beer and one of the largest consumers in the world. Its beer is on par with the best on the international market and it can be found around the globe. For a nation that many still don’t identify as having a high-quality beer tradition, something typically reserved for countries with paler skin tones (perhaps the lingering impact of when Corona was referred to as “piss water”), the rise to this status is remarkable. However, to “celebrate” Mexican Lager by appropriating Mexican culture is wrong.

Diminishing the value of Mexican Lager by saying it’s just like any other adjunct lager is also wrong and offensive. Ashley Rodriguez rightly noted in an article for CraftBeer.com, “to pretend the style has no clear-cut stance is to ignore the way non-Latinx people in the United States perceive – and flatten – Latinx culture.”

Though people who were not Mexican were important in the growth of the brewing industry in Mexico, as the industry grew, Mexicans made it their own. To be clear, there is history, culture, and ingredients that make Mexican Lager unique.

Just as brewers use the labels Japanese Lager, Polish Lager, or Italian Pils, it’s right to identify Mexican Lager as something distinct. Does it constitute a “style”? In certain situations, perhaps not. And that’s fine if it’s treated as equally as other beer cultures.

It’s quite a challenge for a non Mexican-owned brewery that’s not in Mexico itself to represent the character of Mexican Lager in an inoffensive way. Making an adjunct lager and slapping stereotypical Mexican imagery on the label doesn’t cut it.

We should also move past referring to amber Mexican Lagers as being in the Vienna style. Amber lagers from the Czech Republic and Franconia don’t get the same treatment. The only connection amber lagers made in Mexico have to Vienna Lager is the use of lager yeast and color, and even that is questionable. To continue to call these beers “Vienna Lager” is incorrect and diminishes the Mexican tradition of brewing amber lager, which has been more enduring and robust than in the United States or Austria.

Admittedly, some Mexican breweries have referred to Vienna Lager themselves. Though the records show that Mexican breweries did not originally use this term.

The simple fact that Mexico has continually made pale, amber and dark beer is notable. This is different than some other beer cultures around the world. Certainly, compared to the United States, where large breweries do not have a notable production of beer beyond pale lager. It’s a great tradition and one that lends itself to enjoying beer in a variety of situations, whether it be knocking back a cold pale lager on a hot summer day, sipping an amber lager with a spicy taco, or chatting with friends over a dark lager by a fire on a cool night.

— —

Brewers, particularly in the US, need to keep in mind that if their Mexican Lager is not made in Mexico and/or is not made by people of Mexican descent, there must be more thought and intent given before releasing one. Think about where your marketing is directed. If it’s toward white people for Cinco de Mayo, you should reconsider.

Also, there’s no shame in making an American adjunct lager. It’s clearly part of the American brewing tradition, and it’s something to embrace. And you can do so without resorting to the use of cultural imagery and references that are not yours.

Finally, think about channeling your energy toward supporting immigrants from Mexico and beyond.

Notes

1 Cervecería Alemana is one potential exception to this claim. One Hundred Years of Brewing (1903) noted the brewery was run by Eduardo Suendermann, adding “this is probably the only lager beer brewery in Mexico not equipped with a refrigerating machine. Natural ice, from caves, is to be had almost beside the brewery and the cellars of this little plant are in these same caves.” I have found very little documentation on Alemana and its brewing methods.

2 Both editions of One Hundred Years of Brewing note the production by some of Sencilla. According to the book (1903), it is “brewed somewhat like a lager beer, but with less percentage of extract. It is fermented and put into cold storage, being sold at an average age of from four to six weeks, but often within half those periods. The smaller establishments put the sencilla into little casks, or kegs, directly after fermentation, and it is sometimes drunk the same day.”

The lower level of extract meant a lower ABV. Dietsch noted this, referring to Sencilla as a kind of “Dünnbier”, or low-alcohol beer. The mention of cold storage brings another question to the claim that lager brewing was not possible.

3 It should be noted that in One Hundred Years of Brewing (1901) the following is stated regarding the establishment of the Toluca brewery, “in reality the wife of Mr. Graf was the founder of the Toluca brewery, who, together with a Mexican, Luis Mancera, made the first top-fermentation beer, while Mr. Graf was at that time the manager of an oil mill, in which position he accumulated the money with which he afterward went into the brewing business.” Of course, her name is not given, and there are no other accounts of this. This is not meant to suggest it’s not true, just that this is the only account I found. It wouldn’t be a surprise if people wanted to bury the fact that a white woman and a Mexican man started a brewery.